New Year, New Arbitration Act?

The UK’s Arbitration Bill (“Bill”), which was re-introduced by the Labour government in July 2024, was presented to the House of Commons (“HC”) on 6 November 2024, having completed its passage through the House of Lords the same day. Having enjoyed robust review and careful revision to date, and having passed its first reading in the HC without debate, it is hoped that the Bill will have swift passage through the HC and it may even receive Royal Assent by the end of 2024.

In this Legal Insight we explore the state of play of the Bill (sponsored by Lord Ponsonby of Shulbrede) and how it compares to the Conservative Government’s prior Bill which was amended by the Special Public Bill Committee but which did not get enacted before UK Parliament was dissolved on 30 May 2024 (the “Prior Bill”).

There are two main changes to the Bill: (i) an express carve out of the default rule for the law governing the arbitration agreement for non-ICSID investor-State arbitration agreements and (ii) clarificatory amendments about appeals from High Court decisions to the Court of Appeal. Amendments addressing arbitral corruption and costs were also tabled and debated but were subsequently withdrawn. We discuss each of these developments in turn before highlighting the next steps for the Bill.

What’s new in the Bill?

Investor-State Arbitrations – Carve out

The Bill includes a new Section 6A(1) which prescribes that the law of the seat will also govern the arbitration agreement (“AA”) unless parties expressly agree a law applicable to the AA (the “Default Rule”). While this provision was in the Prior Bill, before the Bill was re-introduced by the Labour Government, the prior Government had listened to sector feedback and had amended the Default Rule to ensure that it does “not apply inappropriately to certain investor-state arbitrations.”

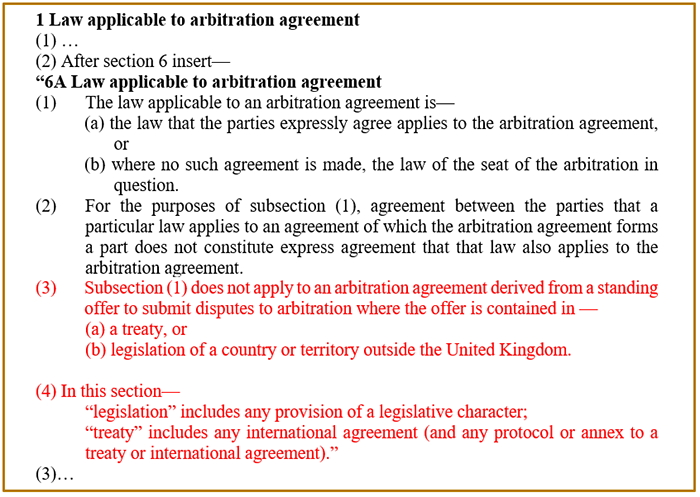

New sections 6A(3) and (4) make it clear that the Default Rule does not apply to AAs derived from standing offers to arbitrate contained in treaties or non-UK legislation. Non-ICSID investor-state AAs, arising out of treaties or non-UK legislation, will therefore not be covered by the Default Rule. However, it should be noted that non-ICSID investor-state agreements arising under commercial contracts will be covered by the Default Rule. It should also be noted, for completeness, that ICSID arbitrations will not be covered by the Default Rule, as they are governed by the ICSID Convention rather than the legislation of particular jurisdictions and they do not have domestic seats. Moreover, the ICSID Convention is incorporated into UK law by the Arbitration (International Investment Disputes) Act 1966, and this carve-out further ensures that, when the UK courts deal with enforcement applications for ICSID awards, there will be no conflict between the two Acts.

The new provisions (in red font) read as follows (clause 1 is only reproduced in part):

Stakeholders in the arbitration community considered it “inappropriate” to apply English law, as a default rule, to the distinct nature of AAs arising within an investment treaty (or foreign domestic investment legislation). Reasons for this included arguments that:

- the applicable law should be determined by arbitral tribunals based on the relevant instruments in each case;

- the fact that tribunals typically apply international law (including principles of treaty interpretation under the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties) and/or foreign domestic laws (depending on the relevant instrument) to issues relating to the arbitration agreement such as its validity and scope;

- the uncertainty resulting from Enka (which sets out the current approach to determining the law of the AA) does not apply to non-ICSID investor-State arbitration in the manner that it applies to commercial arbitration; and

- the risk of overstepping a State's consent with regard to exactly what it signed up to in any particular treaty.

By maintaining the status quo in non-ICSID investor-state arbitration, this carve out should help maintain London as an attractive seat for investment arbitration.

Clause 13 now properly codifies case law on arbitral appeals

Clause 13 in the Prior Bill has been revised by the House of Lords to correctly remedy the drafting error identified in the House of Lords decision of Inco Europe v First Choice Distribution (2000).

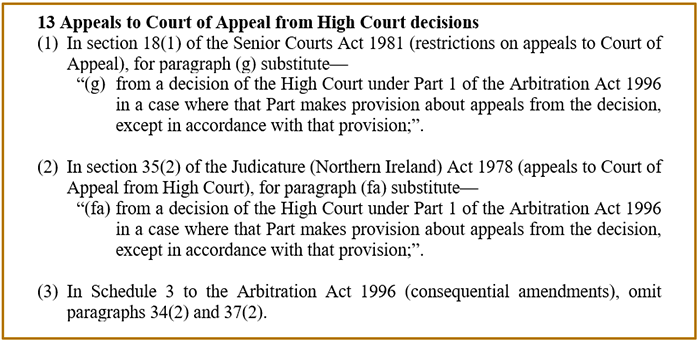

In England and Wales, rights of appeal to the Court of Appeal are governed by the Senior Courts Act 1981 (“1981 Act”), and for Northern Ireland the relevant legislation is the Judicature (Northern Ireland) Act 1978. The Arbitration Act 1996 (“1996 Act”), Schedule 3, paragraphs 34(2) and 37(2), amended those Acts, to say that no appeal was possible under Part 1 except for those sections which expressly required the permission of the High Court. That was incorrect. The correct interpretation of the 1981 Act is that the usual rights to appeal to the Court of Appeal are available under all sections of Part 1 of the 1996 Act except that an appeal requires the High Court’s permission only in the sections which expressly say so.

The Prior Bill picked up the appeals error but confined this point to section 9 (staying legal proceedings in favour of arbitration) which is silent on appeal rights and was the subject matter of the Inco decision, whereas the newly worded Clause 13 highlights that the error impacts the whole of Part 1, not just section 9.

Revised Clause 13 reads as follows:

Amendments debated by the House of Lords which do not feature in the Bill

Corruption in the Arbitral Process

Lord Hacking suggested the insertion of a new general duty at section 33 of the 1996 Act to “safeguard the arbitration proceedings against fraud and corruption”, described as a “very simple measure, which will show the international community that corruption or fraud in all arbitrations where the seat is England is quite unacceptable”. The Lords rejected this proposal. Lord Ponsonby of Shulbrede expressed that our existing legal framework already “well equips the tribunal and courts to deal with corruption”. As arbitrators are under a duty to “act fairly and impartially” and “adopt procedures suitable to the circumstances of the…case” (section 33), a corrupt arbitrator would breach such duties. Other safeguards include section 23 (revocation of an arbitrator’s appointment), section 24 (the court’s power to remove arbitrators) and the loss of arbitrator immunity under section 29 where an arbitrator acts in bad faith (enabling him/her to be sued). Likewise, awards can be challenged under section 68 for serious irregularity and deemed unenforceable as contrary to public policy under section 81. According to the Lords Hansard, none of the leading arbitral institutions supported amending the Bill to strengthen anti-corruption and concerns were raised that a “one-size-fits-all approach would be ineffective and risk unintended consequences”.

Although the amendment was withdrawn, the core message was that the Government will continue to support the sector’s efforts on arbitral corruption, including keeping track of corruption-related initiatives – like the ICC anti-corruption task force – and encouraging quick adoption of best practices as they are developed.

Removal of "costs following the event"

Lord Hacking also sought to amend the “strange phraseology” of “costs following the event” in section 61(2) of the 1996 Act (regarding costs awards) which he said were ancient words not understood by international parties. The other Lords did not agree with his proposal and the proposed amendment was withdrawn. Key reasons for the disagreement include the fact that the Law Commission did not recommend reform to section 61 (stakeholders not having reported that it was causing difficulties in practice) as well as the potential uncertainty it would create.

Key changes implemented by the Bill

We have covered the new changes to the Bill by virtue of parliamentary scrutiny but should you wish to learn about the key changes being implemented by the Bill in general, we discuss these in our November 2023 Legal Insight. We also explore the implications of the Default Rule in our September 2023 Legal Insight.

What’s next for the Bill?

According to UK Parliament’s website, the Bill has been referred to a Second Reading Committee, but the date for this is yet to be announced. Second Readings of non-controversial Bills can be debated in a committee in the Commons, although this is rare. After the Second Reading, the Bill must pass a few additional stages in the HC before the amendments are considered and then the Bill becomes law.

Parliament’s Christmas recess begins on 20 December 2024 so there are three weeks for it to reach the Royal Assent stage. As an uncontroversial bill expected to progress much faster through the HC than it did through the House of Lords, the Bill could become law this year (and we note that its title remains “Arbitration Act 2024”, as opposed to “Arbitration Act 2025”). But if that is not possible, then an Arbitration Act 2025 should arrive as a New Year’s gift early next year.

We have been tracking, and writing about, the Bill since its first draft in September 2023 and will keep monitoring the passage of this legislation and provide relevant updates. You can read our Insights about the reforms to the 1996 Act on our dedicated page here.