Senate Unanimously Holds Corporate Executive in Contempt of Congress for Failing to Comply with a Committee Subpoena

On September 25, the US Senate held a corporate CEO in criminal contempt of Congress after he refused to comply with a subpoena to appear at a congressional hearing. Three days later, the company announced his resignation.

This is the Senate’s first criminal contempt resolution in over 50 years and serves as a stark reminder of the perils facing companies, and their executives, that are entangled in a congressional investigation.

Congressional Subpoenas

Most congressional committees can issue subpoenas to compel the production of documents and witness testimony. In the Senate, subpoenas typically require a majority committee vote or an agreement of both the chairman and the ranking member of the minority party. (One exception is the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, whose chair can issue subpoenas without bipartisan agreement.) As a general matter, Senate committee subpoenas lacking bipartisan support will proceed on a slower pace.

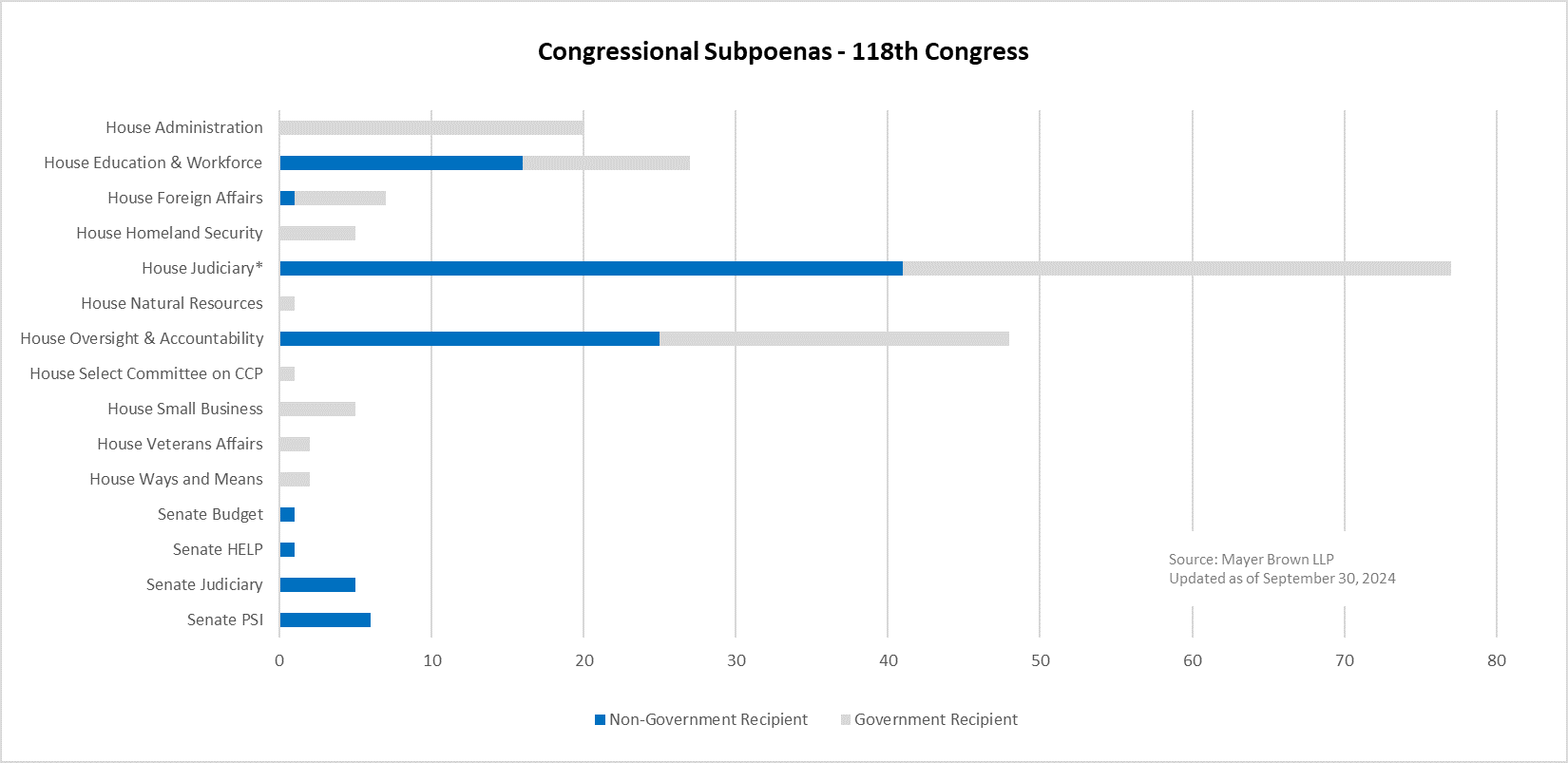

In the US House of Representatives, most committee chairs enjoy unilateral subpoena authority. As a result, subpoenas are often issued more quickly and in greater numbers by House committees, as reflected below.

*Press reports suggest the total number of House Judiciary Committee subpoenas may be significantly higher. These estimates are based on public information. Committees are generally not required to publicize subpoenas.

*Press reports suggest the total number of House Judiciary Committee subpoenas may be significantly higher. These estimates are based on public information. Committees are generally not required to publicize subpoenas.

Enforcement of Congressional Subpoenas

Congress historically punished recalcitrant subpoena recipients or compelled subpoena compliance through its inherent, or implied, legislative power. Under this inherent contempt process, the relevant chamber’s Sergeant-at-Arms would arrest and detain a person who refused to cooperate with an inquiry. This process has not been used in nearly a century and Congress now relies on criminal contempt to punish subpoena recipients for noncompliance and civil litigation to enforce subpoenas.

Under the criminal contempt of Congress statute, first adopted in 1857, it is a misdemeanor criminal offense to “willfully” defy a valid congressional committee subpoena.1 The DC Circuit has held that “willfully” requires a deliberate and intentional refusal to comply and does not require evidence of bad faith.2 The DC Circuit has also held that an advice of counsel defense is unavailable to those facing a contempt of Congress charge.3 Violations of the statute are punishable by a fine up to $100,000 and imprisonment “not less than one month nor more than twelve months.”4

Under the statutory process that governs criminal contempt of Congress, the congressional committee that issued the subpoena will vote on a contempt resolution and refer the resolution to the full House or Senate for consideration.5 If the resolution passes the relevant chamber, the President pro tempore of the Senate or the Speaker of the House will certify and refer the matter to the US Attorney of the appropriate federal district. Under the plain language of the statute, the US Attorney apparently lacks discretion to decline to prosecute the charge as it is his or her “duty …. to bring the matter before the grand jury for its action.”6 Despite the statutory language, the Justice Department has long taken the position that Congress must defer to the Department as to whether a violation of the law has occurred.7 The Justice Department also asserts that an executive branch official who asserts the President’s claim of executive privilege cannot be charged with contempt of Congress.8

While criminal contempt of Congress is considered a punitive measure and not a coercive one, the threat of contempt may encourage compliance with a congressional subpoena. Courts have held that criminal contempt cannot be “cured” by later cooperation with a subpoena, although Congress may choose to certify that further proceedings are unnecessary if compliance with the subpoenas is later obtained.9

To enforce its subpoenas, Congress may turn to the federal courts. A civil contempt statute provides that the Senate can bring a civil action to enforce subpoenas, but generally only for subpoenas issued to nongovernmental recipients.10 The civil contempt statute does not apply to the House of Representatives and the House lacks explicit statutory authority to seek judicial enforcement. Nevertheless, the House’s position is that it may enforce subpoenas against private parties and the executive branch in federal court. Subpoena enforcement litigation by the House of Representatives is authorized through a vote of the full House or a majority vote of the five-member Bipartisan Leadership Advisory Group, comprised of leadership from both parties. The Justice Department does not agree that the House of Representatives may enforce its subpoenas in federal court (a view shared by some federal judges),11 but this issue has yet to be decided by the Supreme Court.

Background of the Dispute

The Senate Health, Education, Labor & Pensions (HELP) Committee has been actively investigating the circumstances around the bankruptcy of Steward Health Care, a private hospital network. In July of this year, the Senate HELP Committee, on a bipartisan basis, issued its first subpoena since 1981, directing Dr. Ralph de la Torre, CEO of Steward Health Care, to appear at a hearing on September 12.

One week before the scheduled hearing date, Dr. de la Torre, through counsel, objected to the subpoena, asserting that his testimony would be inconsistent with an existing bankruptcy court order, would violate a directive from the company barring him from testifying about the bankruptcy, and would violate his constitutional rights. Senate HELP Chairman Bernie Sanders and Ranking Member Bill Cassidy rejected these objections and noted that any Fifth Amendment privilege assertions must be invoked at the hearing on a question-by-question basis.

Dr. de la Torre did not appear at the hearing and his absence was marked with an empty chair at the witness table. One week later, the Senate HELP Committee voted unanimously (with one Senator abstaining) to hold Dr. de la Torre in criminal contempt. On September 25, the full Senate approved the criminal contempt resolution by unanimous consent. The Senate HELP Committee also approved a civil contempt resolution to enforce the subpoena in federal court, but the Senate must adopt that separate resolution before litigation can proceed.

Next Steps

The US Attorney for the District of Columbia will consider whether to present the matter to a grand jury for a criminal indictment. Earlier this year, the Justice Department refused to prosecute Attorney General Merrick Garland in response to a House of Representatives’ criminal contempt vote because the President asserted executive privilege over the materials sought by the subpoena at issue. The Justice Department may well take a different view of a corporate executive who defies a congressional subpoena. In addition, on September 30, Dr. de la Torre sued the Senate HELP Committee (and nearly all of its members), alleging that the subpoena was invalid and the committee’s actions violated his Fifth Amendment rights. This lawsuit must contend with the considerable hurdle of the U.S. Constitution’s Speech or Debate Clause which broadly immunizes members of Congress from suit for legislative acts.

These developments may represent Senators’ increasing willingness to both issue subpoenas and refer non-compliant corporate executives to the Department of Justice for prosecution. They also illustrate the speed with which Congress can escalate subpoena disputes with private parties and the risks of congressional investigations to a company and its executives. Companies should take seriously threats by committees to issue subpoenas and carefully weigh their response to any congressional investigation.

2 United States v. Bannon, 101 F.4th 16 (D.C. Cir. 2024).

4 2 USC. § 192; 18 USC. § 3571(b).

5 2 USC. § 194. The statute contemplates that certification of criminal contempt may, in some circumstances, be available without a full vote of the House or Senate, but that process is disfavored.

7 Prosecutorial Discretion Regarding Citations for Contempt of Congress, 38 Op. O.L.C. 1 (2014).

8 Prosecution for Contempt of Congress of an Executive Branch Official Who Has Asserted a

Claim of Executive Privilege, 8 Op. O.L.C. 101, 102 (1984).

9 United States v. Costello, 198 F.2d 200 (2d Cir. 1952); 4 Deschler’s Precedents of the US House of Representatives, ch. 15, § 21.

11 Comm. on the Judiciary v. McGahn, 973 F.3d 121 (D.C. Cir. 2020) (vacated pending en banc review; appeal dismissed before rehearing en banc).